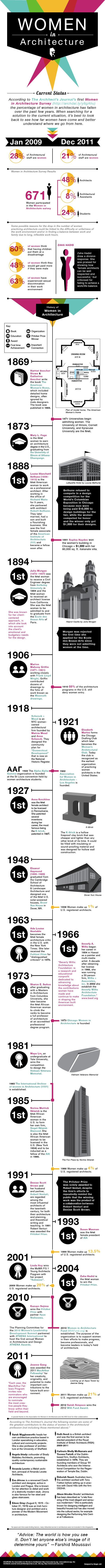

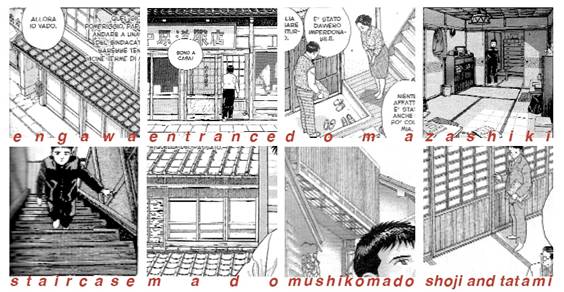

The reading for class this week was “Straight” Women, Queer Texts: Boy-Love Manga and the Rise of a Global Counterpublic by Andrea Wood, which presented me with a very difficult task when it came to a discussion topic. So far each reading has referenced architecture or design in some way and I have been able to develop that specific theme or concept and generate an interesting post directly relating the reading content to my area of interest. This weeks reading however, was focused solely on the purpose of boy-love manga and how it became popular in Japan and the United States: its content, the target audience, and how manga was applied to other forms of literature. The reading was not largely focused on the surrounding environment, though it was referenced in a sense of ambiance and setting the “mood,” but delving deeper, I have discovered that architecture is very prevalent in manga, and even more so in anime, and other interested bodies have done research on this very topic. In my browsing of the world-wide-web I came across a blog dedicated to “Architecture in Anime.” The blogger is an architecture student that loves anime and the posts are simple gifs or images of architecture as it is presented in anime films or television series. Some examples of her posts are below. The collection of images present in the blog illustrates a variety of architecture representative of Japanese design and style. The characters and cultural teachings are clearly rooted in Japanese tradition and it is only right that the architecture be similarly reflective.

http://architectureinanime.tumblr.com/

My search also turned up an article, Japanese City in Manga, by Michela De Domenico, which is more directly related to this week’s reading. The article talks about how today’s Japanese cities signify modernity in manga through architecture. The buildings displayed in backgrounds and the interiors that frame certain environments portray a sense of tradition in the modern setting of manga. Authors of manga were really focused on driving home the point of traditional, Japanese settings; ensuring readers that manga is a Japanese creation and will forever be rooted in Japanese culture, teaching, and lifestyle. According to De Domenico, representing traditional Japanese architecture and design throughout the manga hones in on the well-rounded traditional, Japanese feeling and understanding. (This is generally applied to manga as a whole. Boy-love manga adds a layer of the “unseen” to bring excitement to its pages for its readers.)  http://pendientedemigracion.ucm.es/info/angulo/volumen/Volumen04-2/articulos03.htm

http://pendientedemigracion.ucm.es/info/angulo/volumen/Volumen04-2/articulos03.htm

I went into this post thinking I was at a loss and I was not going to be able to keep with my theme, but the research provided by other interested academics proves that everything is intertwined with purpose and meaning. Manga and Anime are very carefully thought out. Every detail, from a facial expression to what a person is wearing to how a scene is cut in such a way to leave room for imagination, plays into each other to develop the story and set-in-stone the plot, characters, and setting. Architecture, though slightly understated, is not by any means an after thought. The authors and artists need to find architectural and design elements that will help to enhance the scene and the scene’s activity. If “traditional” Manga was set in 19th Century England, would it read the same way? Would the audience get the full feel for the intention of manga? Not likely. It would add a heightened awareness maybe, but also a sense of confusion and misunderstanding. It is likely that it would not be as popular today.